N-Gram Language Model

Contents

- Introduction

- Conditional Probability

- N-Gram Language Model

- Bigrams

- Overcoming Assumptions

- Bigram LM from Tweets

- Performance

- Out of Vocabulary

- Activities

Libraries used

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pylab as plt

from microtc.utils import tweet_iterator

from os.path import join

from collections import Counter, defaultdict

from wordcloud import WordCloud as WC

Installing external libraries

pip install microtc

pip install evomsa

pip install text_models

Introduction

A Language Model (LM) assigns probabilities to words (tokens), sentences, or documents. The direct usage of an LM is to estimate the probability of observing a particular text, it can also be used to generate texts, and in general, it models the dynamics of a language. It is essential to mention that most of the Natural Language Understanding (NLU) tasks rely on an LM.

LM deals with modeling the multivariate probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \mathcal X_2, \ldots, \mathcal X_\ell)\) of observing \(\ell\) words (tokens). As expected, these \(\ell\) random variables are dependent (see the definition of the complement concept, i.e., independence.), and in order to work with them, it is needed to define the concept of conditional probability.

Conditional Probability

The conditional probability of two random variables \(\mathcal X\) and \(\mathcal Y\) is defined as:

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal Y \mid \mathcal X) = \frac{\mathbb P(\mathcal X, \mathcal Y)}{\mathbb P(\mathcal X)},\]if \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X) > 0.\)

The definition allows defining \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X, \mathcal Y) = \mathbb P(\mathcal Y \mid \mathcal X) \mathbb P(\mathcal X),\) which is helpful for two words text. The general case involves \(\ell\) words, which can be defined using the probability chain rule.

\[\begin{eqnarray} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_\ell) &=& \mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 1})\\ \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}) &=& \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1} \mid \mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 2}) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 2}) \\ &\vdots& \\ \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \mathcal X_2) &=& \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2 \mid \mathcal X_1) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1) \end{eqnarray}.\]The first equality of the previous system of equation shows an exciting characteristic; it computes the probability of the next word, \(\ell\), given a history of \(\ell -1\) words; that is

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) = \frac{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_\ell)}{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 1})},\]where \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}) = \sum_x \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}, \mathcal X_\ell = x)\) is the marginal distribution.

N-Gram Language Model

Traditionally, the multivariate probability distributions are fixed with respect to the number of variables; however, the number of words in a sentence or a document is variable. Nonetheless, the dependency between the latest word and the first one on a long text is negligible.

Even when the number of variables is constant, that is, \(\ell\) is kept constant in the model, which has as a consequence that it is not possible to represent a text longer than \(\ell\) words. There is still another concern that comes from estimating the parameters of the multivariate distribution. \(\mathcal X\) is Categorical distributed with \(d\) possible outcomes. The minimum number of examples needed to observe the \(d\) outcomes is \(d^1\); in the case of two variables, i.e., \(\ell=2\), it is needed at least \(d^2\), and in general, for \(\ell\) variables it is needed \(d^\ell\) examples.

The consequence is that for a relatively small \(\ell\), one needs a vast dataset to have enough information to estimate the multivariate distribution. We have seen this behavior in the co-occurrence matrix where most matrix elements are zero; only \(0.021\)% of the matrix is different from zero.

The constraints mentioned above can be handled by approximating the conditional probability of the following word. Instead of using \(\ell - 1\) words to measure the probability of obtaining word \(\ell\), the history is fixed to only include the latest \(n\) words, namely

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) \approx \mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell - n + 1}, \ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell -1}).\]Bigrams

The n-gram LM for \(n-2\) is known as bigram, and its formulation is \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell-1}).\) We have been working extensively with bigrams, albeit in a different direction: finding collocations. In addition, the dataset obtained from the library text_models does not follow the definition of LM bigrams; an LM bigram uses as input two words (tokens) that are consecutive. Conversely, the two words in text_models models did not have an order and were the composition of all the pairs in each tweet.

The bigram model is defined as:

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}) = \frac{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell -1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1})}.\]The procedure to estimate the values of \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell -1}, \mathcal X_\ell)\) and \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1})\) have been described previously. The example seen was a pair of dices where a dependency between \(\mathcal X_r=2\) and \(\mathcal X_c=1\) is wired. This example can be modified to link it closely to a bigram LM by assuming that there is a language with only four words, represented by \(\{0, 1, 2, 3\}\). These words are used to compose bigrams following a Categorical distribution, where the process generating this bivariate distribution is the following.

d = 4

R = np.random.multinomial(1, [1/d] * d, size=10000).argmax(axis=1)

C = np.random.multinomial(1, [1/d] * d, size=10000).argmax(axis=1)

rand = np.random.rand

Z = [[r, 2 if r == 1 and rand() < 0.1 else c]

for r, c in zip(R, C)

if r != c or (r == c and rand() < 0.2)]

It can be observed that the starting point are variables \(\mathcal X_r\) (i.e., \(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1}\)) and \(\mathcal X_c\) (i.e., \(\mathcal X_\ell\)) following a categorical distribution with \(\mathbf p_i = \frac{1}{d}\) where \(d=4\). Then the bivariate distribution is sampled on variable Z where 80% of the examples where \(\mathcal X_r=\mathcal X_c\) are droped and it is induced a dependency for \(\mathcal X_r=1\) and \(\mathcal X_c=2\).

The estimated \(\mathcal P(\mathcal X_r, \mathcal X_c)\) is

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.0149 & 0.0771 & 0.0791 & 0.0782 \\ 0.0663 & 0.0131 & 0.0939 & 0.0730 \\ 0.0810 & 0.0799 & 0.0146 & 0.0796 \\ 0.0797 & 0.0742 & 0.0780 & 0.0172 \\ \end{pmatrix}.\]The marginal distribution \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_r) = (0.249374, 0.246370, 0.255133, 0.249124)\) which can be obtained as follows:

M_r = W.sum(axis=1)

where W contains the estimated bivariate distribution. It is not necessary to obtain the marginal \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_c) = (0.241988, 0.244367, 0.265648, 0.247997)\); however, it is observed that the dependency induce impacts this marginal and not the former.

The conditional \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_c \mid \mathcal X_r)\) can be estimated as

p_l = (W / np.atleast_2d(M_r).T)

and the result is shown in the following matrix

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.0597 & 0.3092 & 0.3173 & 0.3138 \\ 0.2693 & 0.0534 & 0.3811 & 0.2962 \\ 0.3175 & 0.3131 & 0.0574 & 0.3121 \\ 0.3201 & 0.2980 & 0.3131 & 0.0688 \\ \end{pmatrix}.\]Generating Sequences

The conditional probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_c \mid \mathcal X_r)\) (variable p_l) and the marginal probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_r)\) (variable M_r) can be used to generate a text. The example would be more realistic if we used letters instead of indices; this can be done with a mapping between the index and string, as can be seen below.

id2word = {0: 'a', 1: 'b', 2: 'c', 3: 'd'}

It is helpful to define a function (cat) that behaves like a Categorical distribution; this can be done using a Multinomial distribution using the parameters shown in the following code.

cat = lambda x: np.random.multinomial(1, x, 1).argmax()

The requirement to use the conditional probability is that a starting word is needed; the conditional probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_c \mid \mathcal X_r)\) once the value is known of \(\mathcal X_r\). We can assume that the first word can be simulated using the marginal \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_r)\) as can be seen as follows.

w1 = cat(M_r)

Once the starting word is obtained, it is needed to iterate as many times as one wants using the conditional probability to generate the next token; this can be observed in the following code.

l = 25

text = [cat(M_r)]

while len(text) < l:

next = cat(p_l[text[-1]])

text.append(next)

text = " ".join(map(lambda x: id2word[x], text))

The previous code (including the marginal distribution) is executed three times, and the result can be observed in the following table.

| Text |

|---|

| d a d c b d c d c d a b a b c d a d b d a d b c b |

| c a b a c a c d b d d a d c d b d b d b a b a b c |

| b a c b a b a c b d a d c b c d b c d c a c b d c |

Using a Sequence to Estimate \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_r, \mathcal X_c)\)

NLP aims to find and estimate the model that can be used to generate text; therefore, it is unrealistic to have \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{1}, \mathcal X_{2}, \ldots, \mathcal X_\ell)\); however, we can estimate it using examples. Considering that we have a method to generate text, we can generate a long sequence and estimate the bivariate distribution parameters from it.

The first step is to have a mapping from words to numbers. The second step is to retrieve the words, and the third step is to create the bigrams. These can be observed in the following code.

w2id = {v: k for k, v in id2word.items()}

lst = [w2id[x] for x in text.split()]

Z = [[a, b] for a, b in zip(lst, lst[1:])]

The rest of the code we have seen previously; however, it is next to facilitate the reading.

d = len(w2id)

W = np.zeros((d, d))

for r, c in Z:

W[r, c] += 1

W = W / W.sum()

The bivariate distribution estimated from the sequence is presented in the following matrix. It can be observed that the values of this matrix are similar to the matrix used to generate the sequence.

\[\begin{pmatrix} 0.0150 & 0.0750 & 0.0790 & 0.0781 \\ 0.0655 & 0.0113 & 0.0930 & 0.0715 \\ 0.0869 & 0.0808 & 0.0156 & 0.0810 \\ 0.0797 & 0.0743 & 0.0767 & 0.0165 \\ \end{pmatrix}.\]Joint Probability

We have all the elements to compute the joint probability of a particular sequence, for example the probability of observing the sequence a d b c is \(\mathbb P(\text{"a d b c"}) = 0.008885\); this is a simplified notation the complete notation would be \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=a, \mathcal X_2=d, \mathcal X_3=b, \mathcal X_4=c) \approx \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1) \prod_{i=2}^4 \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{i} \mid \mathcal X_{i-1}).\) The following code uses the probability chain rule to estimate the joint probability.

text = 'a d b c'

lst = [w2id[x] for x in text.split()]

p = M_r[lst[0]]

for a, b in zip(lst, lst[1:]):

p *= p_l[a, b]

The previous example is complemented with a sequence that, by definition, it is known that has a lower probability, the sequence differs only in the last word, and its probability is \(\mathbb P(\text{"a d b d"}) = 0.006907.\)

The procedure described presents the process of modeling a language from the beginning; it starts by assuming that the language is generated from a particular algorithm, then the algorithm is used to estimate a bivariate distribution, which is used to produce a sequence. The sequence is an analogy of a text written in natural language, then the sequence is used to estimate a bivariate distribution, and we can compare both distributions to illustrate that even in a simple process, it is unfeasible to obtain two matrices with the same values.

Overcoming Assumptions

However, some components of the previous formulation are unrealistic for modeling a language. The first one is the addition of the possible sequences of a particular length sum to one, e.g., \(\sum_{x,y,z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-2}=x, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}=y, \mathcal X_\ell=z) = 1\). The implication is that there is a probability distribution for every length, which is not a desirable feature for a language model because the length of a sentence is variable.

The second one is that the first word cannot be estimated using the marginal \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_r)\); this distribution does not consider that some words are more frequently used to start a sentence. This effect can be incorporated in the model with a starting symbol, e.g., the sequence a b d would be \(\epsilon\) a b d.

The sum of the probabilities of all possible sentences with three words and a starting symbol can be seen in the following equation.

\[\begin{eqnarray} &&\sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon, \mathcal X_2=x, \mathcal X_3=y, \mathcal X_4=z) \approx \\ &&\sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) =\\ &&\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon) =\\ &&\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \sum_{x, y} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon)\sum_z \mathbb P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) =\\ &&\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \sum_{x} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \sum_y \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x)=\\ &&\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) \sum_{x} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon) = \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon) = 1 \end{eqnarray}\]It can be observed that the inclusion of a starting symbol does not solve the problem that there is a probability distribution for every length.

The third problem detected is that the length of the sentence is a parameter controlled by the person generating the sequence; however, the length of the sentence depends on the content of the sentence, so it is also a random variable. A feasible approach to include this behavior in the model is adding an ending symbol.

The accumulated probability of all the possibilities for a three-word sentence with a starting symbol and ending symbols (i.e., \(\epsilon_s\) and \(\epsilon_e\), respectively), can be expressed as follows:

\[\begin{eqnarray} &&\sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s, \mathcal X_2=x, \mathcal X_3=y, \mathcal X_4=z, \mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e) \approx \\ &&\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s) \sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e \mid \mathcal X_4=z) P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s) \end{eqnarray}\]As can be seen, the procedure used on the equation with the starting symbol is not feasible on the equation at hand; consequently, it is needed to analyze this equation further to figure out how to proceed. The first characteristic to notice is that \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s)=1\). The second one is that the first word is always \(\epsilon_s\); consequently, \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x \mid \mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s) = \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x)\); using these elements, it is obtained:

\[\begin{eqnarray} &&\sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s, \mathcal X_2=x, \mathcal X_3=y, \mathcal X_4=z, \mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e) \approx \\ &&\sum_{x, y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e \mid \mathcal X_4=z) P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y \mid \mathcal X_2=x) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_2=x) = \\ &&\sum_{y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e \mid \mathcal X_4=z) P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \sum_x \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y, \mathcal X_2=x) =\\ &&\sum_{y, z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e \mid \mathcal X_4=z) P(\mathcal X_4=z \mid \mathcal X_3=y) \mathbb P(\mathcal X_3=y) =\\ &&\sum_{z} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_5=\epsilon_e \mid \mathcal X_4=z) \sum_y P(\mathcal X_4=z, \mathcal X_3=y) = P(\mathcal X_5 = \epsilon_e)\\ \end{eqnarray}\]As can be seen, the overall probability does not sum to \(1\); it depends on the probability of choosing the ending symbol.

Bigram LM from Tweets

The simplest model we can create is a bigram LM; the starting point is to have a corpus. -The corpus used in this example is a set of 50,000 tweets written in English.- Once the corpus is obtained, we can use it to estimate the bivariate distribution \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_\ell)\) and use the conditional probability to obtain \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1}).\)

There are different paths to compute \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})\) one of them is using the raw frequency of the words as follows:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) &=& \frac{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{ \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-1})}\\ &=& \frac{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{\sum_i \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)}\\ &=& \frac{\frac{C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{N}}{\frac{\sum_i C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)}{N}} \\ &=& \frac{C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{\sum_i C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)}\\ \end{eqnarray},\]\(C\) is the co-occurrence matrix.

The co-occurrence matrix (variable bigrams) is created with the following code; as can be observed for every tweet, it is included a starting and ending symbol.

fname = join('dataset', 'tweets-2022-01-17.json.gz')

bigrams = Counter()

for text in tweet_iterator(fname):

text = text['text']

words = text.split()

words.insert(0, '<s>')

words.append('</s>')

_ = [(a, b) for a, b in zip(words, words[1:])]

bigrams.update(_)

The term \(\sum_i C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)\) is the frequency of word \(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}\), i.e., \(C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}) = \sum_i C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)\) which corresponds to variable prev in the following code

prev = dict()

for (a, b), v in bigrams.items():

try:

prev[a] += v

except KeyError:

prev[a] = v

We can store \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})\) on a nested dictionary which is the variable P in the following code.

P = defaultdict(Counter)

for (a, b), v in bigrams.items():

next = P[a]

next[b] = v / prev[a]

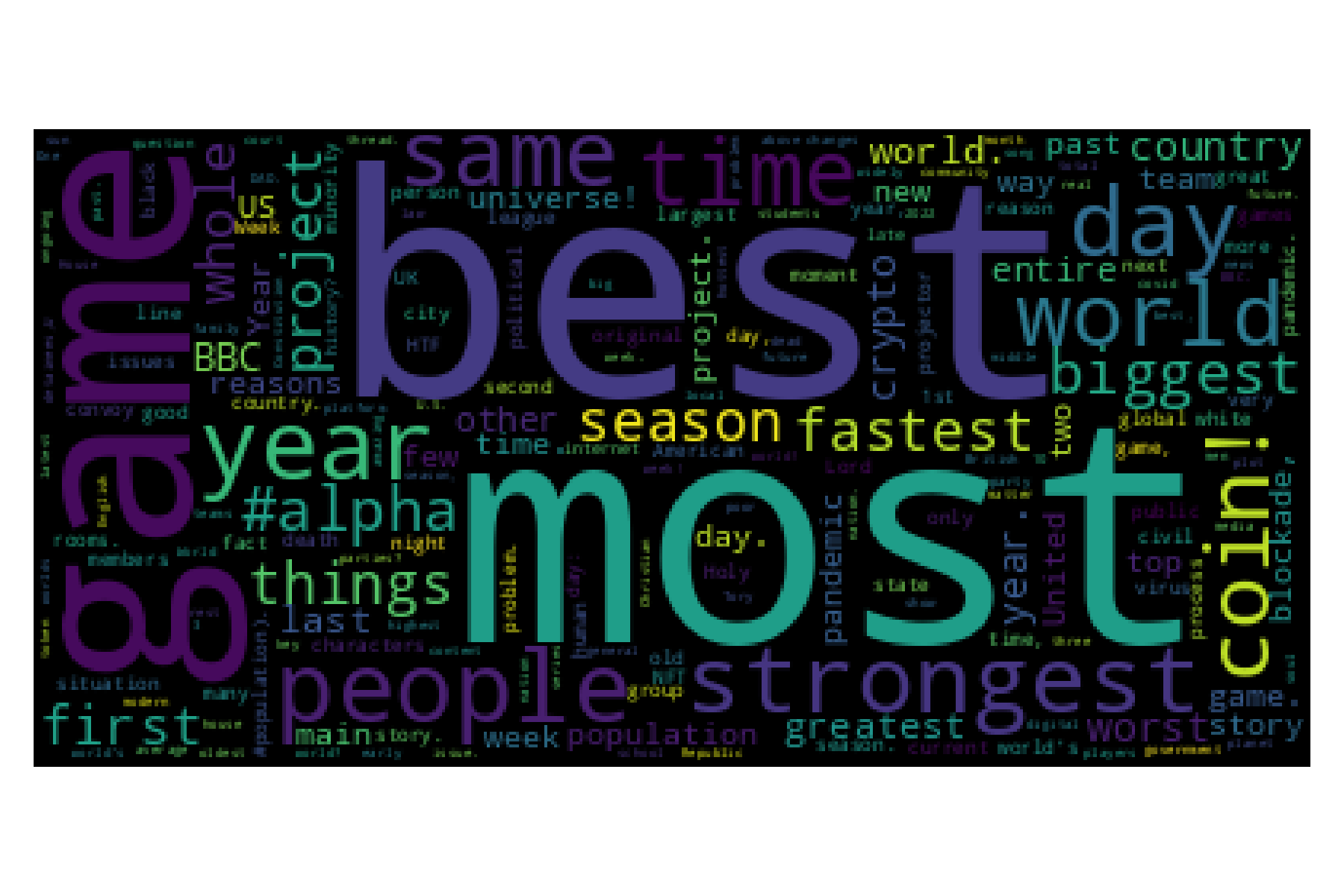

The conditional probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})\) can be used to illustrate which is the most probable word at the starting of a sentence, as seen in the next figure.

Word cloud code

wc = WC().generate_from_frequencies(P['<s>'])

plt.imshow(wc)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

Generating Sequences Section presented an algorithm to generate a sentence given a \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})\); that algorithm can be extended to generate a sentence by considering the starting and ending symbols as can be seen in the following code.

sentence = ['<s>']

while sentence[-1] != '</s>':

var = P[sentence[-1]]

pos = var.most_common(20)

index = np.random.randint(len(pos))

sentence.append(pos[index][0])

The following is an example of a sentence generated with the previous procedure: \(\epsilon_s\) What happened before the one idiot or a few things to me up \(\epsilon_e\).

As we described previously, the probability chained rule can be used to estimate the probability of a sentence. For example, the following code defines a function to compute the joint probability, i.e., the probability of a sentence; the difference between the following implementation and the previous one is the inclusion of the starting and ending symbol.

def joint_prob(sentence):

words = sentence.split()

words.insert(0, '<s>')

words.append('</s>')

tot = 1

for a, b in zip(words, words[1:]):

tot *= P[a][b]

return tot

joint_prob('I like to play football')

8.491041580185946e-12

Performance

This section has been devoted to describing LM and a particular procedure to develop it. The approach has a solid mathematical foundation; however, at the same time, in order to make it feasible, some assumptions have been made. Consequently, one wonders whether those decisions impact the quality of the LM and if they have to what degree. The best way to measure the impact of those decisions is to test the LM on the final application where it is being used; that is used, the metrics developed to test the application, and indirectly measure the impact that has a complex LM in that scenario.

It is not always possible to embed different LM in the final application and test which one is better; another approach is to use a particular performance metric to test the developed LM. The direct approach would be to compute the joint probability in another set and use that measure to compare different LM. However, in practice, the joint probability is not used; instead, it is used Perplexity defined as:

\[PP(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_N) = \sqrt[N]{\frac{1}{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_N)}}.\]The PP of a bigram LM is \(PP(\mathcal X_1, \ldots, \mathcal X_N) = \sqrt[N]{\frac{1}{\mathbb P(\mathcal X_1=\epsilon_s) \prod_{\ell=2}^N \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell} \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})}} = \sqrt[N]{\frac{1}{\prod_{\ell=2}^N \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell} \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1})}}.\) For a moment, let us assume that \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) = c\) is constant for all the bigrams. Under this assumption, the Perprexity is \(\sqrt[N]{\frac{1}{c^{N-1}}}\); however, if \(N\) does not consider the starting symbol which has a probability of \(1\), the Perplexity would be \(\sqrt[N-1]{\frac{1}{c^{N-1}}}=c\) which is more interpretable than the previous equation, and it is related to the branching factor of the language. Consequently, the starting symbol will not contribute to the value of \(N\) in the computation of Perplexity.

The following function computes the Perplexity assuming a sentence or a list of sentences as inputs. The product \(\prod \mathbb P(\mathcal X_{\ell} \mid \mathcal X_{\ell-1})\) is transformed into a sum using the logarithm, and the rest of the operations continue on log space. The last step is to change the result using the exponent.

def PP(sentences,

prob=lambda a, b: P[a][b]):

if isinstance(sentences, str):

sentences = [sentences]

tot, N = 0, 0

for sentence in sentences:

words = sentence.split()

words.insert(0, '<s>')

words.append('</s>')

for a, b in zip(words, words[1:]):

tot += np.log(prob(a, b))

N += (len(words) - 1)

_ = - tot / N

return np.exp(_)

For example, the Perplexity of the sentence I like to play football is:

text = 'I like to play football'

PP(text)

70.01211090353188

The Perplexity of the corpus used to train the LM is:

fname2 = join('dataset', 'tweets-2022-01-17.json.gz')

PP([x['text'] for x in tweet_iterator(fname2)])

66.8740729934466

Another example could be I like to play soccer which is computed as follows.

PP('I like to play soccer')

This example produces a division by zero error; the problem is that the bigram play soccer has not been seen in the training set. However, one would still like to compute the Perplexity of that sentence and, more critically, an LM must model any sentence even though it has not been seen on the training corpus.

Out of Vocabulary

The problem shown in the previous example is known as out of vocabulary. As we know, most of the words are infrequent, which requires training the model on a massive corpus to collect as many words as possible; however, there will not be a sufficiently large dataset for all the cases given that the language evolves and the physical constraints of computing an LM with a corpus with that magnitude. Consequently, the OOV problem must be handled differently.

Traditionally, the approach followed is to reduce the mass given to those words retrieved on the training set and then use that mass in the OOV words. It is mentioned mass because the probability of all events must sum to one, so in the process, we had followed the sum of all words’ probabilities sum to one. That sum cannot be one because there are words that have not been seen.

Laplace Smoothing

One approach is to increase the frequency of all the words in the training corpus by one. The idea is to define a function \(C^\star\) as follows \(C^\star(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) = C(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) + 1\), for the case of bigrams corresponds to \(C^\star(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) = C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) + 1\), where \(C^\star(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}) = \sum_i C^\star(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i) = C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}) + V\), where \(V\) is the vocabulary size counting the unknown word. The method can be implemented with the following code.

V = set()

[[V.add(x) for x in key] for key in bigrams.keys()]

V = len(V) + 1

prev_l = dict()

for (a, b), v in bigrams.items():

try:

prev_l[a] += v

except KeyError:

prev_l[a] = v

P_l = defaultdict(Counter)

for (a, b), v in bigrams.items():

next = P_l[a]

next[b] = (v + 1) / (prev_l[a] + V)

The following table compares the four words more probable given the starting symbol using the approach that does not handle the OOV and using the Laplace smoothing.

| Word | Baseline | Laplace |

|---|---|---|

| I | 0.028640 | 0.004450 |

| The | 0.020600 | 0.003201 |

| This | 0.009020 | 0.001403 |

| A | 0.006780 | 0.001056 |

It can be observed from the table that the probability using the Laplace method is reduced for the same bigram; on the other hand, the mass corresponding to unknown words given the starting symbol is: \(1 - \sum \mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}=\epsilon_s) \approx 0.7541.\)

The Perplexity can be computed using the method described previously; however, the Laplace Smoothing modifies how the conditional probability is calculated. The Perplexity method uses a helper function that is the conditional probability in the standard case. In the Laplace smoothing, the helper function considers the case where the next word is unknown, and even when both words are not known, this can be observed in the following code.

def laplace(a, b):

if a in P_l:

next = P_l[a]

if b in next:

return next[b]

if a in prev_l:

return 1 / (prev_l[a] + V)

return 1 / V

The Perplexity of the sentence I like to play football is higher than that computed previously. On the other hand, the Perplexity of I like to play soccer is \(5342.2\).

PP('I like to play football', prob=laplace)

2954.067962071032

The Perplexity of an LM must be measured on a corpus that has not been seen; for example, its value for the tweets collected on January 10, 2022, is

fname2 = join('dataset', 'tweets-2022-01-10.json.gz')

PP([x['text'] for x in tweet_iterator(fname2)],

prob=laplace)

49563.71966143271

The Perplexity of the corpus used to estimate the parameters is \(30646.76\), which is lower than the Perplexity measured on a test set, which is the expected behavior.

Activities

Laplace smoothing can be modified to change the mass store for the unseen tokens.

Add-\(k\) Smoothing

The idea is to replace \(1\) by a constant \(k\) in \(C^\star\); with this modification \(C^\star\) is defined as: \(C^\star(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) = C(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) + k\). For the case of bigrams, the frequency for the words corresponds to \(C^\star(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}) = \sum_i C^\star(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i) = C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}) + kV.\)

The conditional probability for bigrams is

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell, \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) = \frac{C^\star (\mathcal X_{\ell -1}, \mathcal X_\ell)}{\sum_i C^\star (\mathcal X_{\ell - 1}, \mathcal X_i)} = \frac{C(\mathcal X_{\ell -1}, \mathcal X_\ell) + k}{C(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1}) + kV},\]which can be implemented as follows; where ngrams corresponds to \(C\) and prev is \(C(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1}).\)

def cond_prob(ngrams, prev):

output = defaultdict(Counter)

for (*a, b), v in ngrams.items():

key = tuple(a)

next = output[key]

next[b] = (v + K) / (prev[key] + K * V)

return output

A method to compute \(C(\mathcal X_{\ell} - 1)\) from \(C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)\) is shown below where data corresponds to the later frequency.

def sum_last(data):

output = Counter()

for (*prev, last), v in data.items():

key = tuple(prev)

output.update({key: v})

return output

The constant \(k\) also impacts the procedure used to compute the conditional probability; the difference is the swap between one and \(k\), as observed in the following code.

K = 1

def laplace(a, b):

if a in P_l:

next = P_l[a]

if b in next:

return next[b]

if a in prev_l:

return K / (prev_l[a] + K * len(V))

return K / (len(V) + K * len(V))

The Perplexity of the sentence I like to play soccer can be computed with the following code, the difference is that the parameter \(k\) is set to \(0.1\).

prev_l = sum_last(bigrams)

K = 0.1

P_l = cond_prob(bigrams, prev_l)

PP('I like to play soccer',

prob=lambda a, b: laplace((a, ), b))

1780.7548164607583

Max Smoothing

Different techniques have been proposed to handle missing words on an LM; one similar to \(k\) smoothing is to define \(C^\star\) using the maximum of the frequency or the parameter \(k\), i.e., \(C^\star(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}) = \max(C(\ldots, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_{\ell}), k).\)

The conditional probability for bigrams is

\[\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell, \mid \mathcal X_{\ell -1}) = \frac{\max(C(\mathcal X_{\ell -1}, \mathcal X_\ell), k)}{C(\mathcal X_{\ell - 1}) + k \sum_i \mathbb 1(C(\mathcal X_{\ell-1}, \mathcal X_i)=0)},\]where the denominator can be implemented as:

def sum_last_max(data):

tokens = Counter()

output = Counter()

for (*prev, last), v in data.items():

key = tuple(prev)

output.update({key: v})

tokens.update({key: 1})

for key, v in tokens.items():

output.update({key: K * (V - v)})

return output

and the conditional probabilty corresponds to the following code.

def cond_prob_max(ngrams, prev):

output = defaultdict(Counter)

for (*a, b), v in ngrams.items():

key = tuple(a)

next = output[key]

next[b] = v / prev[key]

return output

The helper function of the Perplexity method corresponds to the following function.

def prob_max(a, b):

if a in P_l:

next = P_l[a]

if b in next:

return next[b]

if a in prev_l:

return K / prev_l[a]

return 1 / V

The Perplexity of the sentence I like to play soccer is obtained with the following code; it can be observed that the Perplexity value is similar using the \(k\) smoothing method and this later one.

K = 0.1

prev_l = sum_last_max(bigrams)

P_l = cond_prob_max(bigrams, prev_l)

PP('I like to play soccer',

prob=lambda a, b: prob_max((a, ), b))

1762.903955247848

From another perspective, the parameter \(k\) in both methods modifies the amount of mass stored to the unseen events, for the case of \(k=0.1\) the mass stored for unseen events is \(1 - \sum \mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell - 1}=\epsilon_s) \approx 0.3269\) which is considerably lower than the one obtained when \(k=1\) which is the standard Laplace Smoothing.

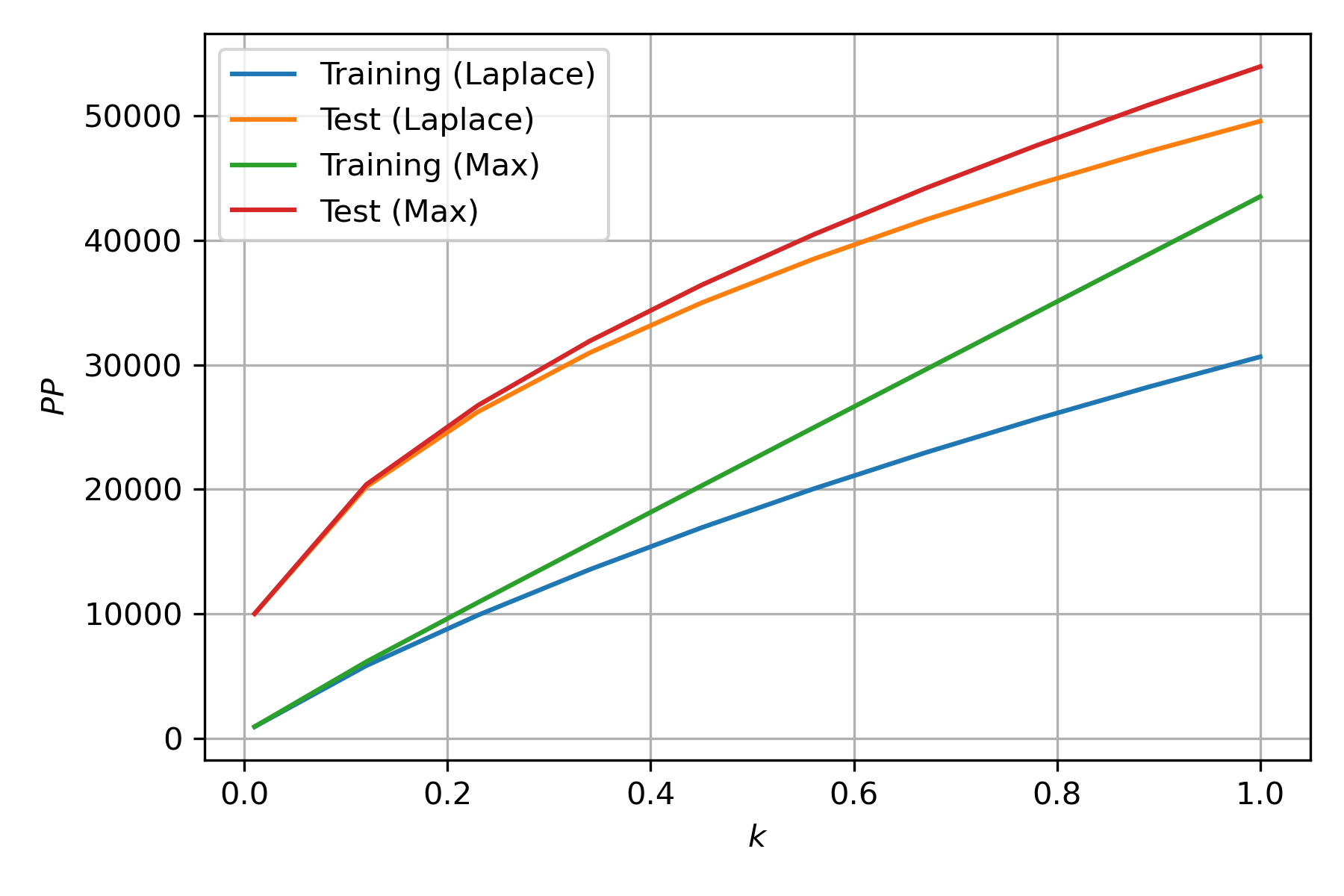

The parameter \(k\) can be varied for different values to illustrate the behavior of Perplexity for different smoothing factors. The following picture presents the Perplexity for different values of \(k\) when \(k\) is in the range from \(0.01\) to \(1\). The values presented are the Perplexity obtained on the training set for the Laplace and Max Smoothing method and the Perplexity on the test set for both methods.

N-Gram

As expected, creating an LM using only bigrams is not enough to model the language’s complexity; however, extending this model is straightforward by increasing the number of words considered. The model can be a trigram LM or a 4-gram model, and so on. However, every time the number of words is increased, there are fewer examples to estimate the joint probability, and even increasing the size of the training set is not enough. Therefore, LMs have changed to a continuous representation instead of a discrete one; this topic will be covered later in the course.

A trigram LM models \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell - 2}, \mathcal X_{\ell -1})\); the first step is to estimate these values from a corpus. The procedure is equivalent to the bigrams being the only difference is that it is needed to add another starting symbol. It can be observed that \(n-1\) starting symbols are used and that the n-grams are computed using function zip and the list comprehension notation.

def compute_ngrams(fname, n=3):

ngrams = Counter()

for text in tweet_iterator(fname):

text = text['text']

words = text.split()

[words.insert(0, '<s>') for _ in range(n - 1)]

words.append('</s>')

_ = [a for a in zip(*(words[i:] for i in range(n)))]

ngrams.update(_)

return ngrams

The Perplexity helper function needs to be updated to compute the n-grams; the procedure is similar to the one used to create the n-grams.

def PP(sentences,

prob=lambda a, b: P_l[a][b], n=3):

if isinstance(sentences, str):

sentences = [sentences]

tot, N = 0, 0

for sentence in sentences:

words = sentence.split()

[words.insert(0, '<s>') for _ in range(n-1)]

words.append('</s>')

tot = 0

for *a, b in zip(*(words[i:] for i in range(n))):

tot += np.log(1 / prob(tuple(a), b))

N += (len(words) - (n - 1))

_ = tot / (len(words) - (n - 1))

return np.exp(_)

At this point, we have all the elements to create an LM of any size; for example, the following code creates a trigram LM using max smoothing.

fname = join('dataset', 'tweets-2022-01-17.json.gz')

ngrams = compute_ngrams(fname, n=3)

V = set()

_ = [[V.add(x) for x in key] for key in ngrams.keys()]

V = len(V) - 1

K = 0.1

prev_l = sum_last_max(ngrams)

P_l = cond_prob_max(ngrams, prev_l)

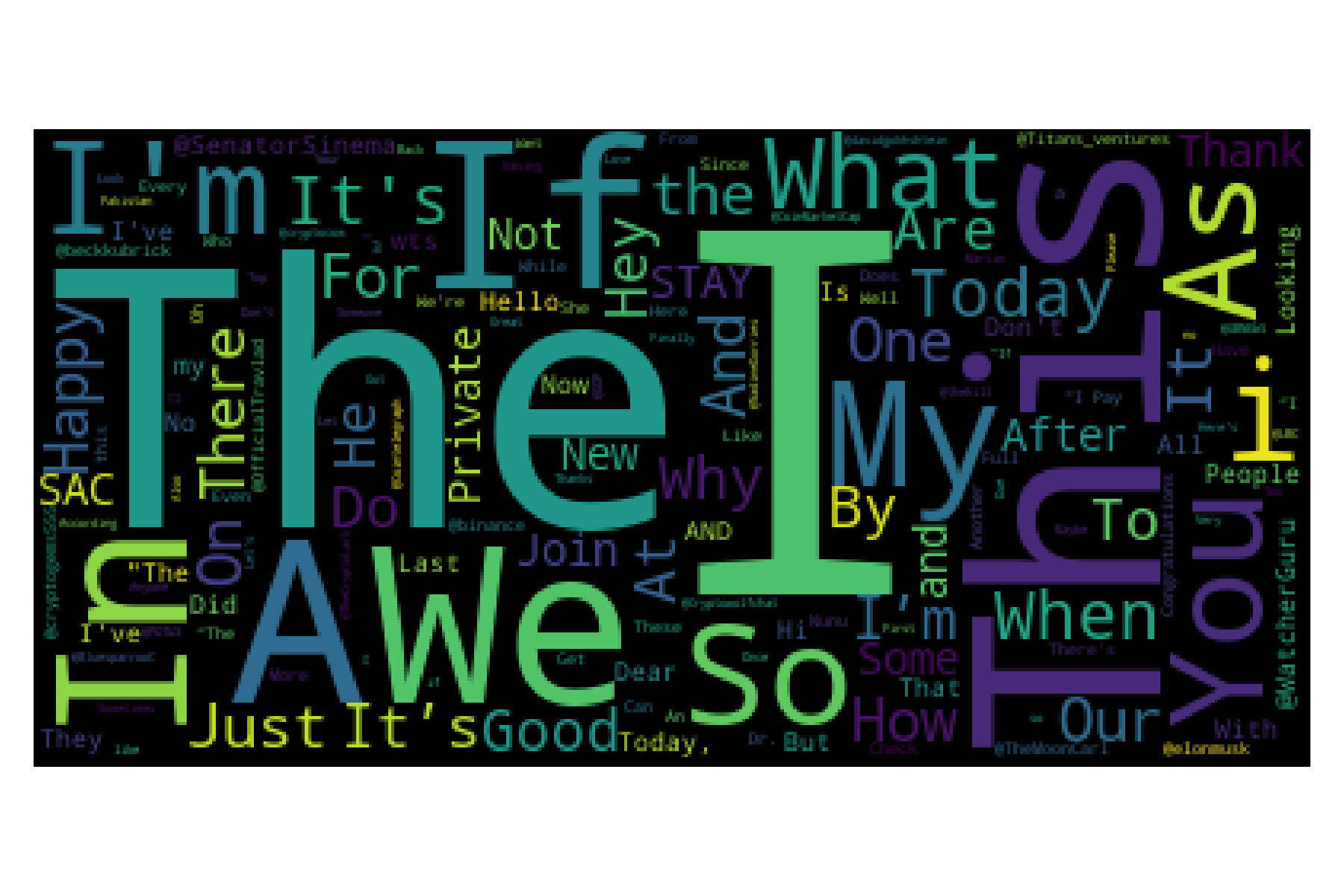

The use of the LM can be illustrated by creating a word cloud of the conditional probability \(\mathbb P(\mathcal X_\ell \mid \mathcal X_{\ell-2}=of, \mathcal X_{\ell-1}=the)\) (i.e., P_l[('of', 'the')]) shown below.